Lomanagh Loop

LOCATION: Sneem

LENGTH: 10.5km

DIFFICULTY: Moderate

PARKING: Sneem North Square

A little bit about the area

Our map does not correspond to exact points or numbered signs along the trail. Instead, this map is seen as a companion for the area, filling you with information on what you might find and where you might find it. It will hopefully add to your enjoyment of this wonderful corner of Iveragh and help build the memories that will stay with you long after you leave.

The Lomanagh Loop Walk starts and ends in Sneem - a beautiful little town that is sometimes overlooked by visitors to Iveragh. Divided by the River Sneem and surrounded by spectacular landscapes, including Kenmare Bay and the Dunkerron Mountains; Sneem is also sprinkled with outdoor gems such as the Garden of the Senses. There is so much to see and do here, and Sneem.ie will give you lots of ideas on where to eat or stay while in the area. The local community newsletter is the perfect place to find out about upcoming events, and to keep up with the many community-driven and eco-friendly initiatives in the town.

The white line follows the Lomanagh Loop Walk, a 10km hiking trail that follows red way-markers which can take around 3.5 hours to complete. The loop follows a mix of tarmac roads, forestry roads and a section through sheep-grazed farmland, which can become boggy underfoot. Due to the presence of livestock, no dogs are permitted on this trail. We recommend sturdy hiking boots and rain gear.

There are many other loop walks and trails around Iveragh, which are only accessible due to the generous permission granted by landowners. You can find out more via the South Kerry Development Partnership page here: South Kerry Trails. The Fermoyle Loop Walk, for example, also begins in Sneem but follows a different route into the hills. We have put together a similar map for that trail, with a focus on the incredible geology of the region. Guided walks along the trails around Sneem are another popular way of experiencing all that this landscape has to offer.

HOW TO EXPERIENCE THE MAPS:

The map locations can be seen on your mobile device. Clicking on the square icon in the top right hand corner of the respective map to open the map in a web browser or Google maps app. Or you can click on the square in the top left of the map to follow it on this page.

TRAIL GUIDE:

Below the maps is the guide for the map and the selected points.

There is also an alternative Storymap:

Lomanagh Loop Guide

-

1. Start/Finish in the North Square

The Lomanagh Loop can be started from the North Square in Sneem. There are public toilets located on Sportsfield Road and several local eateries where you can stock up on some drinks and snacks for the walk. Please remember to take all your rubbish with you and to leave no trace. The centrally located start point for this walk also means that it is ideal for those using public transport. Another major advantage is that, on your return, you won’t have to go far for a meal or well-earned pint!

Staying in Sneem will give you a chance to stroll around and head over the bridge (which has incredible views!) to the South Square and beyond. There are many local businesses to support, whether your interest is in local crafts or beautiful floral arrangements. The relaxed pace of Sneem is a welcome change and the town wears its community spirit proudly on its sleeve.

-

2. Sneem Sculpture Trail

You might have noticed the Charles de Gaulle Memorial in the Fair Green, North Square. The ex-president of France visited Sneem shortly after leaving his post in 1969. His connection to the town came from his wife’s nanny, who hailed from Sneem. This memorial is part of the Sneem Sculpture Trail; this route takes you to see various monuments and sculptures and is a great way to explore the town.

Learn about Steve ‘Crusher’ Casey – one of Ireland’s greatest sportsmen and a Sneem native. His 6’4” stature and physical prowess undoubtedly benefited from the manual work he undertook in the local Templenoe forestry – once stepping in to haul a load after the draft horse assigned the role had become too exhausted!

In another presidential connection, a number of the sculptures around Sneem have connections to Cearbhall Ó’Dálaigh. The 5th president of Ireland (1974-76) spent the final years of his life living in Sneem. One of the more unusual sculptures is that of a panda which was a gift from the People’s Republic of China in memory of Ó’Dálaigh and to honour his work with the Irish Chinese Cultural Society. A clip from the RTÉ News archive showing the unveiling of the panda sculpture in 1986 makes for nostalgic viewing.

3. River Wildlife

Near the start of the loop walk, you pass a section of the River Sneem; you can get a nice viewing point from just behind the GAA pitch. The river plays a huge part in the landscape of Sneem, cutting through the middle of the town before flowing into Kenmare Bay.

Whether it’s watching a raging flood or listening to a gentle babbling brook, a river can be hypnotic. The varying speed and volume of water can affect the types of wildlife you find too. A gentle, shallow section might be the spot to look for Dippers (Gabha Dubh). Dark brown with a white breast, these small birds can be seen dipping and bobbing along the water’s edge before ducking under the flow, emerging with a beak full of aquatic insects.

Deeper pools are the places to look for Kingfishers (Cruidín). Arguably Ireland’s most colourful bird, if you can find a kingfisher’s fishing post you are in for something amazing. They will often use these favoured perches to return to again and again, patiently waiting for the flash of a fish beneath the surface below and ‘splash!’ – they plunge like a neon knife into the water.

Much of the life around rivers is possible due to the invertebrates that inhabit the riverbed or the vegetation on the riverbank. They are food for many birds and fish which, in turn, feed larger fish and other animals. The abundance and variety of these invertebrates – larvae, worms, flies, etc. – is a good indicator of how healthy a river system is. Rivers which are affected by pollutants, such as sewage or run-off from farmland are home to fewer invertebrates which, in turn, affects the other wildlife on the river.

The Pearl Mussel Project has been working in Kerry to protect the rare Freshwater Pearl Mussel. The Blackwater, Caragh and Currane river catchments on Iveragh are home to nearly 50% of Ireland’s remaining Freshwater Pearl Mussels (Diúilicín Péarla Fionnuisce), which shows just how important the region’s waterways are for this unique species. The Pearl Mussel Project has put together some wonderful educational resources on this species, and on biodiversity in general, which you can find here.

-

4. Songbirds

If walking the trail in spring, be sure to take some quiet moments to sit and listen to the birdsong. Many have just arrived from long migrations, often from far off areas such as Southern Africa. While it may be tricky to see the singer, their melodious songs are a delightful declaration of their presence. The delicate descending notes of a Willow Warbler (Ceolaire Sailí) and the onomatopoeic calls of the Chiffchaff (Tiuf-teaf) or Cuckoo (Cuach) can be heard around Iveragh come spring.

A bird that is rarely seen but has a giveaway call is that of the Grasshopper Warbler (Ceolaire Casarnaí). As the name suggests, this tiny light-brown coloured bird has a call that closely resembles that of a grasshopper. While not as musical as some of its neighbours, it’s worth listening to just how long they are calling for. To show their fitness to potential mates or to deter rivals, these birds hold their notes for incredible durations. The grasshopper warbler call above was recorded on the trail in April and the bird held this note for over 30 seconds! Impressive!

If you like the great outdoors and birds, then why not consider contributing to one of Birdwatch Ireland’s ongoing bird surveys such as the Countryside Bird Survey or the Irish Wetland Bird Survey. It’s a great way to help protect our wildlife while spending time in nature.

-

5. Mountain Building

Looking to the hills, the incredible Dunkerron Mountain Range rises to the north of the trail. This mountain belt stretches from Waterville in the west all the way to the MacGillycuddy’s Reeks in the east. The mountain building event that formed the Dunkerron Mountains is known as the ‘Variscan Orogeny’, and its signature is preserved in mountains across Europe, Asia, and Northern America.

The Dunkerrons are monuments of a collision event which occurred when Laurussia, the continental plate carrying Ireland, collided with other continents of the time to form the ‘supercontinent’, known as Pangaea. These mountains are composed of the Old Red Sandstones that were deposited during the Devonian Period. Across the mountains the original flat-lying bedding layers of the Old Red Sandstones remain visible, however, these layers have been overturned to almost unbelievable angles, which is testament to the immensity of geological forces.

During the continental collision, enormous amounts of compression forced rocks in the collisional zone to lift upwards, buckle, and fold into mountains. The uplift of the Dunkerron Mountains was at its maximum rate around 320 to 290 million years ago.

6. Hedgerow Habitats

Photo 13-15

Travelling the Lomanagh Loop will highlight the importance of Irish hedgerow habitats, as this is where you see much of the flora and fauna on the trail. Depending on the time of year, juicy blackberries will be on the menu for many birds in autumn, or green leaves for hungry caterpillars in spring. The food chain of a hedgerow is long and complex: the leaf is eaten by a Caterpillar (Bolb), which falls prey to a Spider (Damhán Alla), which is hunted by a Lizard (Laghairt Choiteann), that gets caught by a Stonechat (Caislín Cloch), which is plucked from its perch by a Kestrel (Pocaire Gaoithe)! The possibilities are endless!

Spring is a particularly busy time for life in our hedgerows. Many of our birds choose to nest in the safety of the thick vegetation and the nectar rich flowers are crucial for our pollinators. Ireland has a wonderful array of native wildflowers and trees - with the hedgerow becoming one of the last safe refuges for many of these species.

The loss of connectivity between these areas is known as ‘habitat fragmentation’. This process of reducing, clearing or converting our wild areas, such as hedgerows, results in plants and wildlife being separated from their mates or food sources. Animals need corridors of connectivity between habitats to move safely; without these they are vulnerable to predation, starvation or road traffic collisions.

You can watch a wonderful National Biodiversity Data Centre video with dairy farmer John Fogarty here. Listening to how he maintains his hedgerows as both storm shelters for his animals and as a haven for nature is inspiring. A second video shows how hedgerow biodiversity and pollinators have benefited the mixed farm of Sean O’Farrell.

-

7. Spring Flowers

Lomanagh is a great trail to keep an eye out for spring flora. It’s something we look forward to each year – the first pops of floral colour that brighten the landscape and herald the arrival of spring.

One species that is found in a number of areas along the trail is Colt’s Foot (Sponc), a vibrant yellow relative of the Dandelion (Caisearbhán). The large heart shaped leaves and reddish tinge to the scaled stalks help to separate it from the dandelion.

One of the first purple flowers to emerge is that of the Dog-violet. There are two species to look for: the Early Dog-violet (Sailchuach Luath) and the Common Dog-violet (Fanaigse), the latter having a white spur at the back of the flower-head while the former has a purple spur. You can read more about what to look for in our 'Spring on Iveragh' section.

It’s also great to look into the Irish names of flowers you find when out and about. There is often so much more detail or folklore connected to the Irish names. Take the Lesser Celandine, or Grán Arcáin, for example, which translates to ‘piglet’s grain’. This is a reference to the grain like growths on the roots of the flower resembling that of pig feed.

Wildflowers of Ireland is a handy website to help with identification, finding the Irish name and interesting nuggets of information. For some fascinating floral folklore, check out Niall Mac Coitir’s book ‘Ireland’s Wild Plants’.

-

8. Conifer Forestry

The planting of non-native conifer plantations in upland areas is controversial. These woods are often very low in biodiversity, are planted in areas that hosted valuable native habitats (such as moors or bogs), and the soils that remain after the conifers have been harvested is often too acidic for much regrowth.

However, conifer plantations – such as that found at Lomanagh – are not completely devoid of wildlife. Many of our smaller bird species call these habitats home. The smallest bird in Ireland is the Goldcrest (Cíorbhuí), and it can be found to take advantage of the buffet of Spiders (Damhán Alla) that weave their webs in the needled branches of Pines (Péine) or Spruce (Sprús) trees. Smaller than a Wren (Dreoilín), their excited pipping calls can be heard when on the move and you may glimpse a flash of their golden-striped heads which lends to their name.

A more unusual bird to look for in Lomanagh is the Crossbill (Crosghob). A large member of the finch family, the male plumage is rusty red while females are a grey and green mix. The most unique aspect of these birds is the very specialised shape to their beaks – the upper and lower bills end in a long point which overlaps at the front. They act like shears to make quick work of opening a conifer cone to access the fatty seeds inside. March is an especially good time to look for them as they are one of the earliest birds to breed in Ireland.

While they have not (yet!) been recorded in Lomanagh on the National Biodiversity Data Centre’s maps, it might still be worth keeping a look out for both Red Squirrels (Iora Rua) and Pine Martens (Cat Crainn), as they have been sighted in other parts of Sneem. A UCC study showed that both of these elusive Irish mammals take up territories in conifer plantations. Be sure to record your sightings here if you do see any.

-

9. Lizards, Newts and Frogs

Another secretive group of Iveragh’s wildlife - reptiles and amphibians - are present around Sneem. The Common Lizard (Laghairt Choiteann) is Ireland’s only native reptile; south-facing banks and upland areas are some of the best places to look for them. Hibernating during the coldest of our winter weather and basking during our sunniest spells helps them to regulate their body temperature.

Perhaps the most amazing thing about these little lizards is that they give birth to live young, rather than lay eggs like most reptiles. Arriving from mid-summer, these fully developed mini-lizards are ready to go from day one. We have lots of information on lizards on our website, including fun activities for children and some helpful tips on searching for them.

One animal that is easily confused with lizards is our Smooth Newt (Earc Sléibhe). An amphibian rather than a reptile, they have a similar appearance to lizards but on closer inspection you will see they have smooth skin and move slowly on land, whereas lizards have scales and are quicker. We have created a handy infographic for you to help tell them apart.

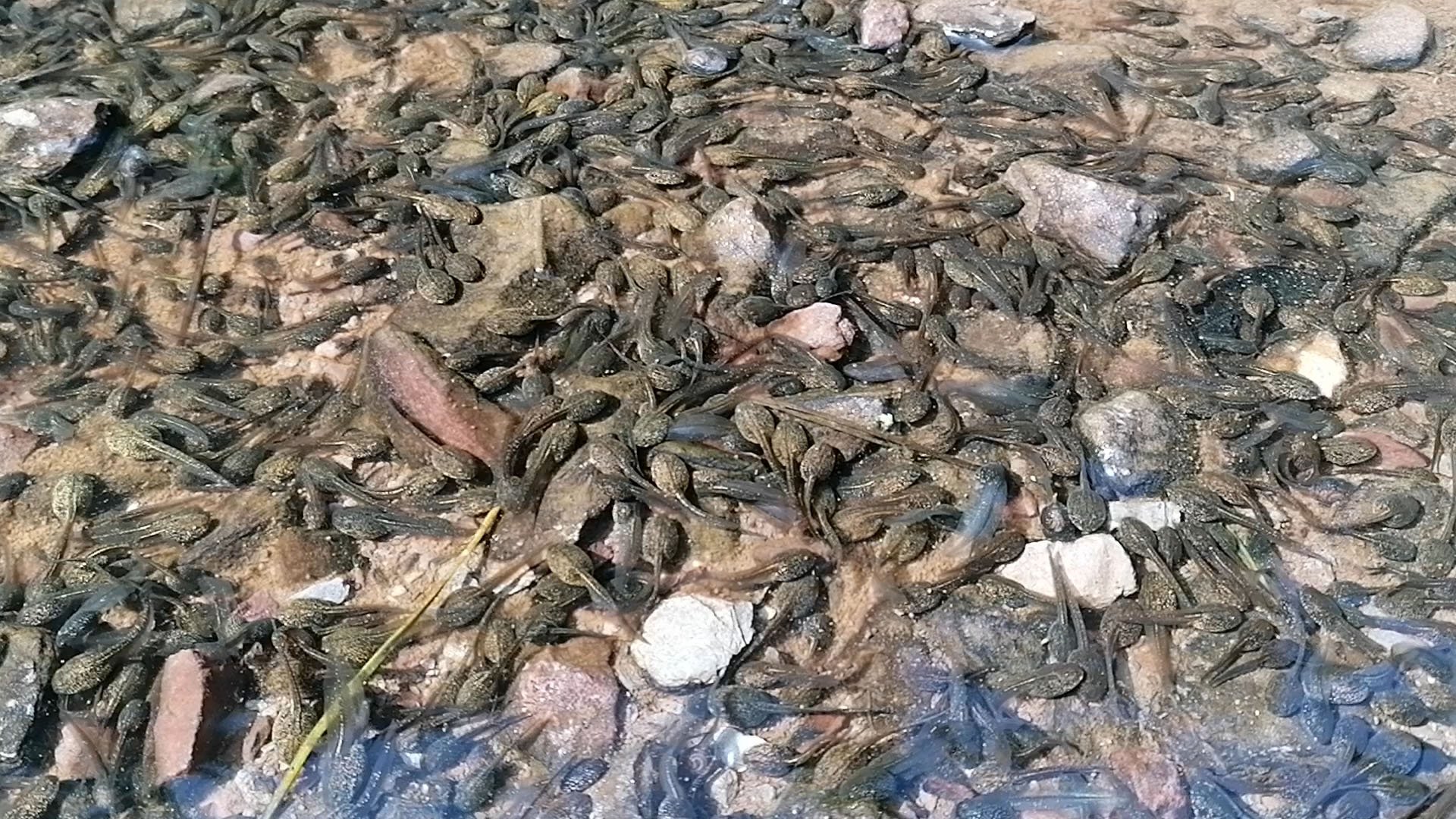

Spring is a great time to keep an eye on pools and ponds, as newts begin the mating season by moving from land into freshwater. This is also the time of year when Frogs (Frog) mate – also by gathering in pools and ponds where their raucous mating croaks fill the air before frogspawn clumps begin to appear.

Iveragh is also home to the very rare Natterjack Toad (Cnádán); they can be found around Derrynane and Castlemaine Harbour. You can read more about our reptile and amphibian friends in our Spring on Iveragh section.

-

10. Glaciation

By the Quaternary, our present geological period which began 2.6 million years ago, Ireland had completed its northward drift from the equator and obtained its present geographic position. Around this time the global climate began to alternate between warmer periods and periods of extreme cold. During the cold periods, large ice sheets covered much of Ireland. The glacial deposits and features of the Iveragh Peninsula mostly come from the most recent glacial period, which was at its maximum extent around 25,000-20,000 years ago. At that time, much of southwest Ireland was occupied by an ice body which radiated outwards from a dispersal centre near the head of the Kenmare River. Ice from this centre spread out westwards across Sneem before continuing offshore into the Atlantic. While difficult to imagine, these ice sheets were likely over 500m thick and only the tallest mountain peaks would have protruded above the ice.

These ice sheets had largely retreated from low-lying ground by 14,000 years ago, but not before ravaging the landscape to leave behind the rugged terrain we see around Sneem today. Corries, moraines, roches moutonées and other glacial features are also scattered across the region. You can learn lots more about glaciation and other geological features from our Fermoyle Loop Map here.

-

11. Then and Now

The rugged landscape surrounding Sneem has a long history of human inhabitation, with evidence that includes ancient ruins of stone dwellings and rock art in the hills. While the meaning and origin of some of these art symbols are unknown, they can often be linked to early settlers marking their lands, or the points along paths or trade routes.

High levels of rainfall and the wet, rocky, mountainous terrain mean that farming on the Iveragh Peninsula can be very challenging. For many generations, cattle and sheep which are well-suited to this type of terrain were reared here and brought to market. Booleying is the practice of moving animals from upland to lowland grazing with the seasons and this was a common practice across much of the Iveragh Peninsula. Other sources of income included forestry work, fishing, construction, or road works before tourism created additional opportunities.

An 1851 census shows the Sneem population to be 1,694, but the famine and desire to emigrate to find employment reduced this number over the years. Although the current population is around 500, the rising popularity of leaving cities for the countryside and the increased capacity to work from home may see further rejuvenation of the area.

Electricity arrived to the area in 1951 and those ESB workers may never have imagined what the future would hold for Sneem. The Sneem Digital Hub is an initiative to encourage remote working by providing reliable digital infrastructure and community support to those relocating to the area. The coastal scenery, outdoor activities and community initiatives all lend to Sneem becoming one of the most attractive options for an Iveragh getaway, or maybe even something more permanent.

-

12. What's in a Name

Like so many Irish place names, ‘Sneem’ doesn’t appear to mean much until you look at the original Irish name. Sneem is so often disregarded as ‘an odd name’ by many, but it is the anglicised version of ‘An tSnaighm’ – the knot. While the exact reason for ‘the knot’ is not known, two plausible theories have been put forward. We’ve already mentioned the North and South Squares of Sneem, separated by the River Sneem and connected by a bridge. Perhaps the bridge and two squares could be considered a knot if imagined from above?

The idea behind the second theory can be seen by watching the water from the end of Quay Road (Bóthar na Cé). From here you will see the mouth of the River Sneem spill into Kenmare Bay, twisting and spinning around the rocky outcrops. The churning of these waters form sinuous turbulent knots visible at the surface and is a strong contender for the source of the Irish name.

Another story that may be heard is that Sneem is ‘the knot in the Ring of Kerry’. However, this is more likely a title awarded after the fact, as the name Sneem is recorded as early as 1756 – indicating its origins are much older than the name ‘Ring of Kerry’.

An Lománach has become Lomanagh and translates to ‘the bare place’. One of the most striking aspects of the area is the dramatic geology of the surrounding hills. Here, large sheets of Old Red Sandstones bear the scars of ancient glacial battles and unimaginable geological events that turned and folded the bedrock like bread dough. This landscape was clearly a notable feature when being identified by early local settlers.

These Irish names are so important and it’s always worth looking for their meanings to reveal more of our local history. Logainm.ie is a great website to look up places based on their original Irish names – from towns to mountains or archaeological sites.

13. The Sneem Community

Spend some time in Sneem and one thing becomes clear: this is a town with a great community spirit. There are traces of various eco-friendly projects all over - from colourful murals and sculptures to a newly installed drinking water filter on the bridge (great for topping up before heading off on the Lomanagh Loop!).

There is a clear love of pollinators, with outdoor areas left unmown to create blankets of wildflowers for our hungry bees and their friends. Outdoor spaces are cherished and a wander along the riverbank will take you by Pyramids, bird-friendly zones and the beautiful ‘Garden of the Senses’. The latter even has a popular allotment which is a wonderful amenity for many locals.

Future projects include ongoing pollinator-friendly additions, an art trail and a wonderful initiative to make Sneem a more autism friendly town. While visiting the region it’s great to play your part too – remember that Sneem is home to local residents all year round, so we ask that you respect their beautiful town and surrounding landscapes while enjoying the region.